TRAVEL MAGAZINE ARTICLE

The Sands of Time: Travels in Egypt

FROM THE AIR, Egypt is sand: sand-colored mountains, sand-colored rocks, sand-colored buildings, sand-colored wonders of the ancient world. If not for their enormous size, even the pyramids would blend right into the desert. The Sahara dominates the landscape of this country, permitting only narrow strips of green on the banks of the Nile. And these plots of fertile soil are where Egyptians have taken a stand against the desert, countering the serene vastness of the Sahara with thriving, vibrant cities for more than 5,000 years.

One step outside of the Cairo airport and the calm of the flight explodes into the crowded bustle of one of the biggest cities in the world. Our tour guide parts a sea of turban-wearing locals jammed up against the doors of the baggage-claim area in order to clear the way to our shuttle. Less than half an hour in this country and I’m already thankful for someone who knows their way around.

The momentary calm of sitting in the airport parking lot evaporates as we pull out into the frantic Cairo traffic. Drivers ignore the center line and stoplights imported from the Western world in favor of weaving and zooming their dented Peugeots, Fiats and minivans in and out of tight spots, with inches to spare. “As for traffic rules,” explains Ehab, our host from the airport to our hotel, “we have no rules. Those lines in the middle of the road make nice decorations.”

Down the Nile in Esna, and at every other tourist port, cruise-ship captains command their vessels with similar abandon… and similar skill. More than 200 ships ferry tourists up and down the Nile. At any given port, 50 of them may line up about as close as Christmas shoppers in a mall parking lot. Imagine five 250-foot luxury boats docked right next to each other in several rows along the pier. (We often had to walk through the lobbies of two or three ships to reach ours.) Then imagine that the one in the middle has to go somewhere. The ensuing traffic jam resembles a fleet of 18-wheelers pulling into the same rest stop.

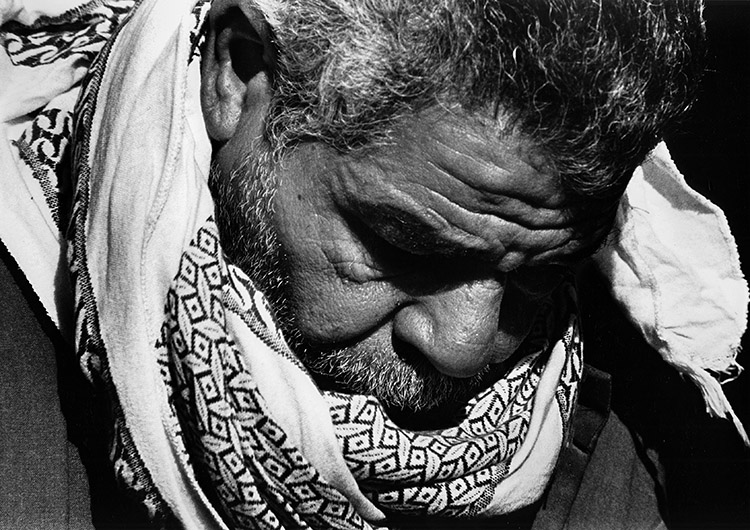

Yet for all the seeming disorganization — punctuated by horn-blowing, shouting and waving — in Cairo traffic as well as on the Nile, the Egyptians exude a relaxed confidence that allows them to master the chaos. And the organizing force of this national demeanor is Islam.

Five times a day, close to 90 percent of Egypt’s population stops everything in order to pray to Allah. From the cruiseship crew praying even as their boat is in the midst of docking to shop owners who leave their registers unattended during afternoon prayers, Islam dictates the daily rhythms throughout this region.

This Islamic influence is most pronounced during Ramadan. Muslims don’t eat, drink or smoke from sunrise to sunset, and many restaurants and bars stay closed during the daytime.

Shorter business hours and thus earlier traffic jams — everyone rushes to get home before dusk — also mark the observation of this month-long celebration. Yes, celebration. Because when the Muslims finally do eat their first meal of the day, they are ready to have a good time.

After dark, traffic slows to a trickle on the elevated highways that cut through the city, but the narrow, winding streets below become a teeming mass of people eating, bartering, socializing and smoking hookahs late into the night. According to one Cairo resident, the party goes on until dawn, when the fast starts again.

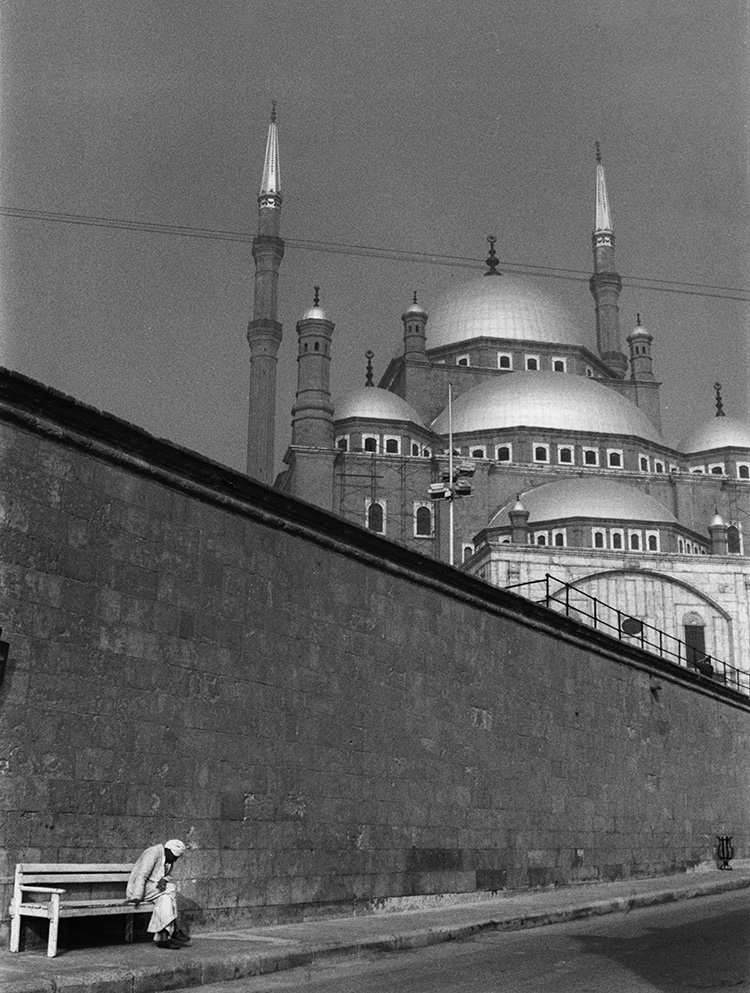

Cairo has strived to maintain its Muslim character in the face of foreign challenges. In A.D. 1176, Muslim leader Saladin constructed a huge wall around the fortress known as the Citadel to protect the city against the Crusaders. Through the years, many of Saladin’s original buildings have been destroyed, but his stronghold remained the center of Egyptian government until the mid-19th century.

Today, the alabaster minarets and silver domes of the Muhammad ‘Ali Mosque jut into the Cairo skyline from within the Citadel, looming far above neighboring palaces and museums. Although not as spectacular as similar mosques in Turkey, this is a dramatic building with ornate decorations inside that also affords a great view of the city.

A short walk from the alabaster mosque, the older and more distinctly Egyptian Sultan Hassan Mosque has a spacious courtyard and a restored mausoleum with gilded-gold walls and inlaid-marble floors.

These mosques — combined with our guide’s crash course in Islam as we toured them — serve as a cursory introduction to Islam and a key step toward understanding modern-day Egyptians.

Since the initial Arab occupation in the seventh century, their religious traditions have held fast through Turkish, French and British occupations. Yet Egyptians have changed with the times. Adaptions to the modern world include tinny speakers that now broadcast the call to worship from minarets, as well as the ever-present TV broadcast from Mecca. Adaptions to the ancient world include the development of a booming tourism industry.

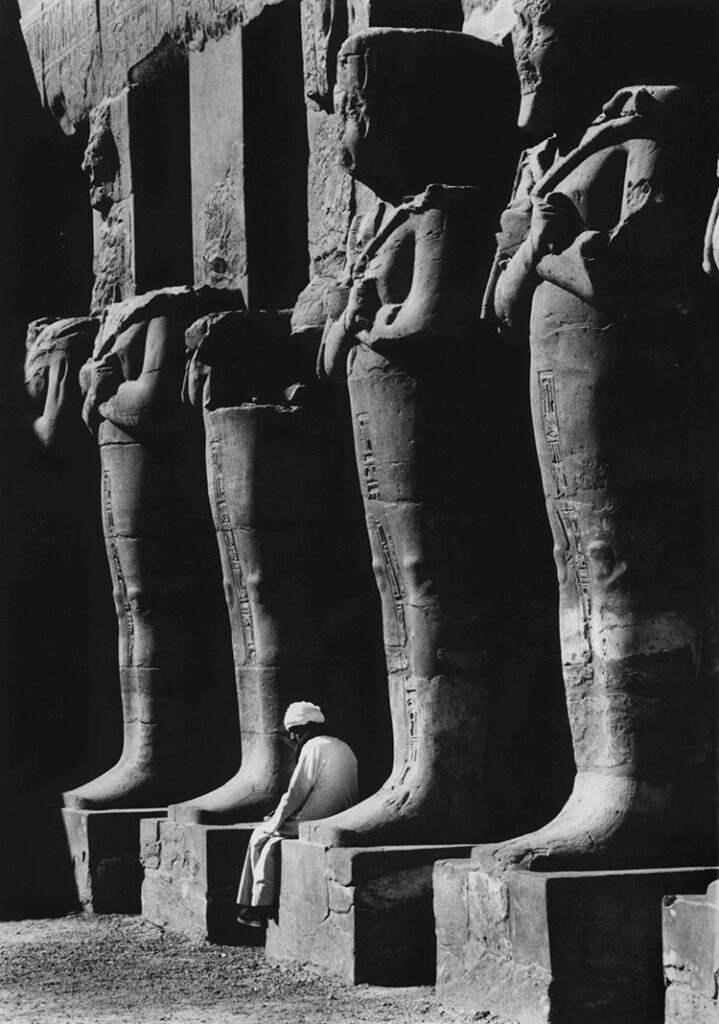

The earth-tone scarves and caftans (the bright-red and purple robes are strictly for tourists) worn by camel drivers at the Giza pyramids and excavation workers at the Temple of Horus in Edfu make for interesting photos. Yet Ramses II and his followers did not dress like this. This is present-day Egypt, dominated by Muslims.

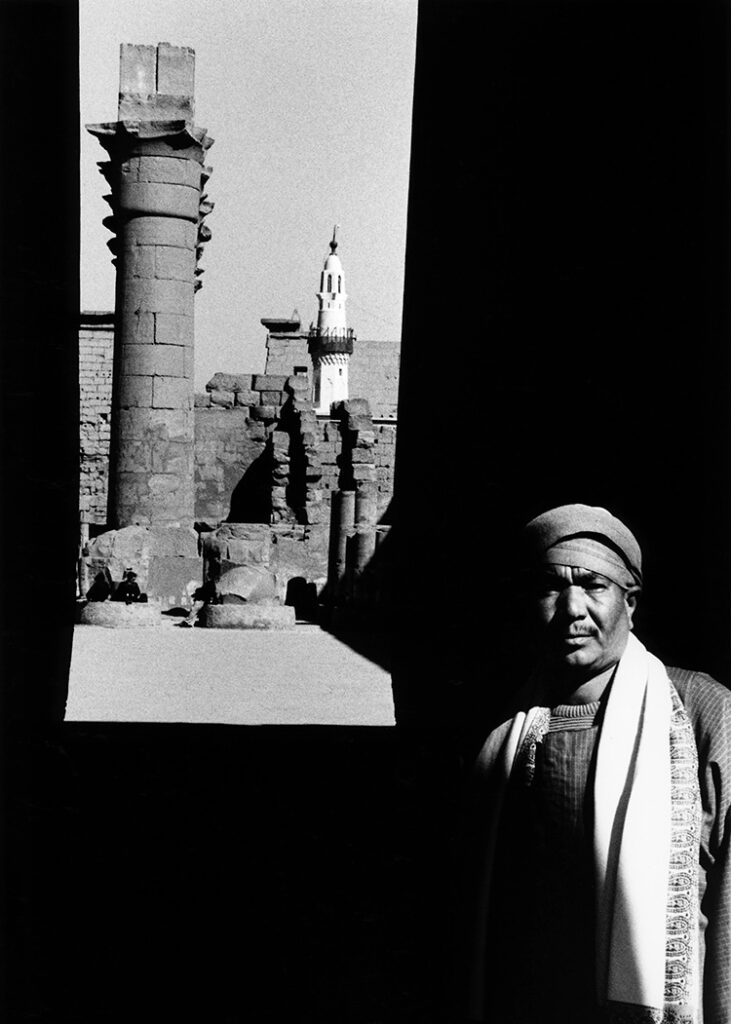

This mix of ancient and modern cultures is nowhere more apparent than the Temple of Luxor. Here, among the 3,000-year-old columns and chapels dedicated to the ancient gods Amun-Re, Mut and Khonsu, stands the Abu al-Haggag Mosque, built during the 12th century. A small white-and-pale-blue mosque with one minaret not even as tall as the main temple colonnade, this structure looks completely out of place. Yet locals have refused to let archaeologists tear it down in order to finish excavating the temple: The almighty Allah triumphs over the old gods.

A much more subtle but equally powerful example of Muslim supremacy lurks within the buildings of the Arab era. An empty, rundown Cairo mosque far from any tour itinerary revealed the secret. On my last day in Cairo, I hired a cab driver for a day of sightseeing. Upon hearing that I’d already visited the Citadel and the pyramids, he drove past a series of nondescript schools and statues. When we came to a stop in front of a dilapidated mosque, I stayed in the cab as my driver negotiated an entry fee with the caretaker.

The interior resembled that of the Sultan Hassan Mosque … but without the restorations and tourists. In fact, nothing seemed very memorable until we were on our way out. Then my driver mumbled something and pointed to my shoes. I looked down and saw that both my laces were tied, then looked back at him. He insisted I look back down. Then I saw it.

There, imprisoned among the other stone blocks that comprised the entryway, lay a block covered in hieroglyphs. A cartouche with waves, birds and stars, letters of the ancient world held captive in a deserted mosque. One sacred building destroyed to make another from a very different culture.

Ancient sites all over Egypt have contributed stones to newer buildings, even the pyramids sacrificed to create the sprawling city that now threatens to engulf them. Most of the white limestone that originally covered the Great Pyramid had been stripped away long ago for use in nearby construction projects.

As the Pizza Huts and luxury hotels of Cairo creep closer and closer to these great ruins, one wonders how much longer the ancient world can hold out against the modern one. Yet the Egypt of today knows better than to undercut its most popular attractions. No minarets on top of the pyramids. Not for now anyway.

That’s because Ramses and Tutankhamen have been making a comeback. From the Polish archaeologists who have worked to reconstruct the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut to the University of Chicago’s ambitious project cataloging every artifact of ancient Egypt, ancient rulers have been getting the respect they once commanded.

Native Egyptians have begun to reclaim their proud history from the Western researchers and scientists so dedicated to its restoration. The Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo is full of young students sketching and discussing the exhibits. A growing percentage of guides are born and raised here, fluent in languages ranging from French and German to Japanese. Ashrif, our guide, spoke perfect English, learned en route to university degrees in English literature and Egyptian history.

For all of his enlightening lectures and charming asides, Ashrif gave the tour our most poignant insight into Muslim culture without saying a word.

After arriving at the Kom Ombo Temple just before sunset, we hurried to tour the waterfront site before dark. As the sun disappeared in a purple haze over the Nile, Ashrif was still showing us around the temple while the crew back on the boat ate their first meal since sunrise. He began talking faster, looking a bit forlorn. At this point, a Christian priest wearing a white robe appeared from behind one of the enormous columns of the temple, walked up to our guide, and offered a date and a cup of water.

At first, Ashrif refused, pointing out the tour group, trying to hold off eating until he finished with us. But when we encouraged him, he quietly ate the date and drank the water as we watched him break his fast with mute fascination, feeling like we had taken part in a sacred ritual.

Local Christians often help Muslims during Ramadan, according to Ashrif. They offer food as well as assistance, looking after their stores, restaurants and other Islamic businesses during prayers. But do they just materialize in a time of need, or do Christians have a permanent community of their own? In this world of Islam, a follower of Jesus seems about as rare as an oasis in the middle of the Sahara.

Where are these elusive Christians, and how can I get in touch with them? The answer came to me in the lobby of the Ramses Hilton in Cairo.

On the evening of Dec. 23, I had settled into a comfortable couch to finish writing a few last-minute postcards. Then it started. First a couple of kids with their parents. Then a few more, some wearing green-and-red sweaters and reindeer horns. Soon, more than 150 Egyptians were packed into the lobby. A hefty older man with a fake white beard began passing out blinking elf hats and fresh apples … and even a few presents.

A flier in my room promoted a Christmas party that evening, but I had expected three carolers and a drink special, not the spectacle now before me. These people seemed quite earnest and enthusiastic.

A choir of about 30 kids in white gowns began singing holiday classics in English, backed by a band including the standard bells and tambourines but also an electric guitar and bongo drums. The adults had their eyes glued to a jumbo-size screen mounted on the glass elevator behind the kids, following along with the words to “Jingle Bells” and “Rudolph, the Red-nosed Reindeer” in both English and Arabic. Most of the hotel guests ignored this little party, disappearing for a moment behind the chorus of “Silent Night” on their way up to the second-floor supper buffet.

A few curious Americans hovered at the back of the crowd. Although the partiers asked everyone in the lobby to join in, this was quite obviously a personal event to these people, not just a crass trip to the big hotel to entertain the Hilton guests. Why then choose this hotel? Perhaps for the Christmas decorations already in place. Or because they felt a common bond with the Western guests. Or maybe they just couldn’t find a church to host the party. This is Egypt after all, dominated by Muslims.